If you have ever had concerns about your child’s speech and language development, you’ve probably been asked at some point, “Have you had their hearing tested?”. In my experience, the most common response is, “No, but I know their hearing is fine”. Do you? Because, here’s the thing. Hearing loss doesn’t necessarily mean you can’t hear!

Hearing is a very complex process. Your ears do some pretty amazing work apart from holding your sunglasses in place and showcasing those fancy earrings. There is a complex organisation of bones, hairs, nerves and cells, that pick up sound waves, process them and send them to your brain. What’s more, this all happens in real time, meaning the system operates almost instantaneously. See? Pretty amazing!

So even if your child turns around when you call them, startles when they hear a loud clap of thunder, or comes running from another room at the faintest sound of a packet of biscuits being opened, that doesn’t necessarily mean that their hearing is perfectly fine.

Oh but my baby had their hearing tested at birth and it was fine so there’s nothing to worry about! Again… not so fast! A hearing loss can be present at or soon after birth, which is why the newborn hearing screenings are so important. This is known as a congenital hearing loss.

However, a hearing loss can also present later. This is known as an acquired hearing loss, which is why you cannot treat the newborn screening as a permanent indicator of hearing ability! Here’s why…

Parts of the ear…

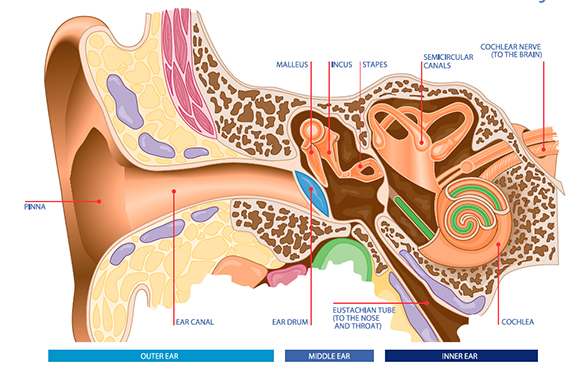

The ear can be divided up into three parts leading up to the brain:

The outer ear is made up of skin and cartilage on the outside, and the ear canal that leads down to the eardrum. Sound travels down the ear canal, striking the eardrum and causing it to move or vibrate.

The middle ear begins at the eardrum, about 2.5 centimetres inside the head. It contains a chain of three tiny bones (ossicles) which link the eardrum to a tiny bony structure in the inner ear called the cochlea. Vibrations from the eardrum cause the ossicles to vibrate which, in turn, creates movement of the fluid in the inner ear.

The inner ear (cochlea) is filled with liquid that carries the vibrations to thousands of tiny hair cells. The movement in the fluid causes the cells to carry a signal up the auditory nerve to the brain. The brain then interprets these signals as sound. This part of the ear also controls balance.

A hearing loss occurs when there is a problem somewhere along this pathway. A problem may arise in any of the outer, middle or inner parts of the ear, or in the complex auditory nerve pathway to the brain.

Types of hearing loss…

There are three basic types of hearing loss: Conductive, Sensorineural and Mixed.

- Conductive Hearing Loss:

This occurs when there is a blockage or damage in the outer ear, middle ear or both. This makes sounds softer and less easy to hear. Some of the causes of a conductive hearing loss include ear infections, “glue ear”, fluid in the middle ear from colds or allergies, perforated ear drum or blockage of the ear canal by wax or foreign objects. The degree of a conductive hearing loss varies, but you cannot go completely deaf. This type of hearing loss can often be treated medically or surgically.

- Sensorineural Hearing Loss:

This occurs when there is damage to, or malformation of the inner ear (cochlea) or the nerve pathways from the inner ear to the brain. It reduces the ability to hear faint sounds and the ability to hear louder sounds clearly. In most circumstances, a sensorineural hearing loss is permanent. It cannot be medically or surgically corrected, therefore hearing devices are often recommended. Some causes include ageing, excessive noise exposure, diseases such as meningitis, viruses such as mumps or measles and head trauma.

- Mixed Hearing Loss:

This occurs when there are problems in both the conductive pathway (in the outer or middle ear) and in the nerve pathway (the inner ear).

An important note about ear infections…

Middle ear infections (Acute Otitis Media) are among the most common illnesses during childhood and can be painful but are not usually serious. They can occur in one or both ears and many children will have at least one acute ear infection by the time they turn 1 year old.

Ear infections are very common in children because the passage between the middle ear and the back of the throat (Eustachian Tube) is smaller and more horizontal in children than in adults. This allows it to be more easily blocked, which means that the secretions (such as those that accompany a cold) cannot be drained from the middle ear into the throat. Secretions and associated bacteria then build up inside the middle ear and can become inflamed.

While some children with an ear infection have no change in their hearing, other children may have a short-term hearing loss. Fluid in the middle ear makes it harder for your child to hear sounds because of conductive hearing loss. It’s helpful to imagine it as if you were trying to hear something underwater. You can still hear, but the sounds are muffled. That is what it might sound like to your child.

The hearing loss may go away once the fluid is gone from the middle ear, although this can take months. However, when ear infections occur over and over again, permanent damage can occur. Children who have recurrent ear infections may develop ‘glue ear’. Glue ear is when children have sticky fluid in their middle ear behind the ear drum that can last for many weeks or months. Therefore, it is critical that ear infections be treated properly.

Sometimes children get fluid in their middle ear but don’t have an infection. This is called otitis media with fluid. You may also hear or see the term “otitis media with effusion” or “fluid in the middle ear.” Cases of fluid in the middle ear (that do not involve an actual infection) present a special problem because symptoms of pain and fever are usually not present. Weeks and even months can go by before parents suspect a problem. When fluid is present in the ear for a prolonged period of time, this can pose a risk of hearing loss and the child may miss out on some of the information that can influence speech and language development.

Degrees of hearing loss…

Many people assume that since their child can hear, they do not have a hearing loss. This is not always the case. There are different degrees of hearing loss ranging from mild to very severe. The degree or severity of the loss is a reflection of the impact it has on your everyday life. A person with normal hearing is able to hear very soft sounds such as leaves rustling or a soft whisper (10 -20 dB).

Mild Loss: 21–45 dB

There might be some difficulty hearing soft speech and conversations, but people with a mild loss are capable of hearing voices clearly in quiet situations.

Moderate Loss: 46–65 dB

Conversational speech will be hard to hear, more so when background noise is present, such as in a classroom, or at home when the television is on.

Severe Loss: 66–90 dB

Normal conversational speech is inaudible but will be assisted by a hearing device. The clarity of speech heard is likely to be significantly affected and visual cues will assist in understanding speech.

Profound Loss: 91 dB +

There is great inconsistency in the benefit derived from a hearing device. Some people may be able to understand clear speech when face to face and in places with good auditory conditions when wearing a hearing device. But others will find it impossible.

Configuration of the loss…

There’s more to hearing than just how loud a sound is. The configuration of hearing loss refers to the shape and pattern of the loss across different frequencies (tones). For example, a hearing loss that only affects high tones would be described as a high frequency loss. This means that there is good hearing in the low tones (e.g. a tuba) but poor hearing in the higher frequencies (e.g birds chirping). A hearing loss that only affects low tones is a low frequency hearing loss. A hearing loss that affects low and high frequencies equally, is known as having a flat configuration.

This is important because speech sounds fall across both the low and high frequencies. The “Speech banana” image on the audiogram chart below gives you an idea of where different sounds fit within various frequencies. So if a child has a high frequency loss, they will miss hearing sounds such as “f”, “s” and “th” in speech. If they have a low frequency loss, sounds such as “m”, “j” and “b” may be missed.

Other descriptors…

· Bilateral vs unilateral

A bilateral hearing loss means there is a hearing loss in both ears. A unilateral hearing loss means that hearing is normal in one ear but there is a loss in the other ear, which can range from a mild to very severe. Children with a unilateral hearing loss are at higher risk for having academic, speech and language, and social-emotional difficulties than their normal hearing peers. This may be because unilateral hearing loss is often not identified and therefore the children do not receive any intervention.

· Symmetrical vs asymmetrical

Symmetrical means the degree and configuration of hearing loss are the same in each ear. Asymmetrical means the degree and configuration are different in each ear.

· Progressive vs sudden hearing loss

Progressive means that hearing loss becomes worse over time. Sudden means that the loss happens quickly. Such a hearing loss requires immediate medical attention to determine its cause and treatment.

· Fluctuating vs stable hearing loss

Fluctuating means hearing loss that changes over time—sometimes getting better, sometimes getting worse. Stable hearing loss does not change over time and remains the same.

Effects of Hearing Loss on Development…

We know that hearing is critical to a child’s speech and language development, communication and learning. Children use their hearing to learn about the world around them. Unfortunately though, children with hearing difficulties continue to slip through the cracks.

The earlier hearing loss occurs in a child’s life, the more serious the effects on the child’s development. Similarly, the earlier the problem is identified and intervention begun, the less serious the ultimate impact.

There are four major ways in which hearing loss affects children:

- It causes delay in the development of receptive and expressive communication skills (speech and language).

- The speech and language deficit causes learning problems that result in reduced academic achievement.

- Communication difficulties often lead to social isolation and poor self-concept.

- It may have an impact on vocational choices.

Children who are hard of hearing will find it much more difficult than children who have normal hearing to learn vocabulary, grammar, word order, idiomatic expressions, and other aspects of verbal communication.

In terms of speaking, children with hearing loss often cannot hear quiet speech sounds such as “s,” “sh,” “f,” “t,” and “k” and therefore do not include them in their speech. Thus, speech may be difficult to understand. Children with hearing loss may not hear their own voices when they speak. They may speak too loudly or not loud enough. They may have a speaking pitch that is too high. They may sound like they are mumbling because of poor stress, poor inflection, or poor rate of speaking.

Should I have my child’s hearing tested?

You should speak to your doctor about having your child’s hearing assessed by an Audiologist if you notice your child does any of the following…

- Responds to sounds inconsistently

- Has delayed speech and/or language development

- Has unclear speech

- Has the volume up high on the TV, iPad etc

- Does not follow instructions well

- Often says “What?”, “Huh?” or looks blank

- Does not respond when called

- Has frequent ear infections

Follow this link for more information from Australian Hearing about how hearing is assessed in young children.

Let’s wrap this up…

Am i trying to send everyone into panic stations by suggesting that every child has a hearing loss? No! What i am hoping though, is that this information will help people understand why it’s not so simple to say “Yes my child’s hearing is fine” if you haven’t had it checked recently.

Don’t forget to Like Modern Speechie on Facebook for more information and tips to help your child be the best communicator they can be!

Please note:

This information is intended to be used to support, not replace, discussion with your doctor or healthcare professionals.